- Home

- Milan Kundera

Farewell Waltz Page 9

Farewell Waltz Read online

Page 9

"I wouldn't take anything back," said Jakub, "because you didn't become a father against your will!"

"Certainly not. I became a father by my own free will and by the good will of Doctor Skreta."

The doctor nodded with an air of satisfaction and declared that he too had a notion of fatherhood different from Jakub's, as shown, by the way, by the blessed state of his dear Suzy. "The only thing," he added, "that puzzles me a bit about procreation is how senselessly parents choose each other. It's incredible what hideous-looking individuals decide to procreate. They probably imagine that the burden of ugliness will be lighter if they share it with their descendants."

Bertlef called Dr. Skreta's viewpoint aesthetic racism: "Don't forget that not only was Socrates ugly but also that many famous women lovers did not distinguish themselves at all by their physical perfection. Aesthetic racism is almost always a sign of inexperience. Those who have not made their way far enough into the world of amorous delights judge women only by what can be seen. But those who really know women understand that the eye reveals only a minute fraction of what a woman can offer us. When God bade mankind be fruitful and multiply, Doctor, He was thinking of the ugly as well as of the beautiful. I am

convinced, I might add, that the aesthetic criterion does not come from God but from the devil. In paradise no distinction was made between ugliness and beauty."

Jakub reentered the conversation, asserting that aesthetic considerations played no part in the loathing he felt for procreation. "But I can cite ten other reasons for not being a father."

"What are they? I am curious."

"First of all, I don't like motherhood," said Jakub, and he broke off pensively. "Our century has already unmasked all myths. Childhood has long ceased to be an age of innocence. Freud discovered infant sexuality and told us all about Oedipus. Only Jocasta remains untouchable; no one dares tear off her veil. Motherhood is the last and greatest taboo, the one that harbors the most grievous curse. There is no stronger bond than the one that shackles mother to child. This bond cripples the child's soul forever and prepares for the mother, when her son has grown up, the most cruel of all the griefs of love. I say that motherhood is a curse, and I refuse to contribute to it."

"Next!" said Bertlef.

"Another reason I don't want to add to the number of mothers," said Jakub with some embarrassment, "is that I love the female body, and I am disgusted by the thought of my beloved's breast becoming a milk-bag."

"Next! "said Bertlef.

"The doctor here will certainly confirm that physicians and nurses treat women hospitalized after an aborted pregnancy more harshly than those who have

given birth, and show some contempt toward them even though they themselves will, at least once in their lives, need a similar operation. But for them it's a reflex stronger than any kind of thought, because the cult of procreation is an imperative of nature. That's why it's useless to look for the slightest rational argument in natalist propaganda. Do you perhaps think it's the voice of Jesus you're hearing in the natalist morality of the church? Do you think it's the voice of Marx you're hearing in the natalist propaganda of the Communist state? Impelled merely by the desire to perpetuate the species, mankind will end up smothering itself on its small planet. But the natalist propaganda mill grinds on, and the public is moved to tears by pictures of nursing mothers and infants making faces. It disgusts me. It chills me to think that, along with millions of other enthusiasts, I could be bending over a cradle with a silly smile."

"Next!" said Bertlef.

"And of course I also have to ask myself what sort of world I'd be sending my child into. School soon takes him away to stuff his head with the falsehoods I've fought in vain against all my life. Should I see my son become a conformist fool? Or should I instill my own ideas into him and see him suffer because he'll be dragged into the same conflicts I was?"

"Next!" said Bertlef.

"And of course I also have to think of myself. In this country children pay for their parents' disobedience, and parents for their children's disobedience. How

many young people have been denied education because their parents fell into disgrace? And how many parents have chosen permanent cowardice for the sole purpose of preventing harm to their children? Anyone who wants to preserve at least some freedom here shouldn't have children," Jakub said, and fell into silence.

"You still need five more reasons to complete your decalogue," said Bertlef.

"The last reason carries so much weight that it counts for five," said Jakub. "Having a child is to show an absolute accord with mankind. If I have a child, it's as though I'm saying: I was born and have tasted life and declare it so good that it merits being duplicated."

"And you have not found life to be good?" asked Bertlef.

Jakub tried to be precise, and said cautiously: "All I know is that I could never say with complete conviction: Man is a wonderful being and I want to reproduce him."

"That's because you've only known life in its worst aspect," said Dr. Skreta. "You've never known how to live. You've always thought that it was your duty to be, as they say, in the thick of things. In the core of reality. But what was that reality for you? Politics. And politics is what is least essential and least precious in life. Politics is the dirty foam on the surface of the river, while the life of the river is lived much deeper. The study of female fertility has been going on for thousands of years. It's had a solid, steady history. And it's

quite indifferent to which government it is that happens to be in power. When I put on a rubber glove and examine a female organ, I'm much nearer the core of life than you, who nearly lost your life because you were concerned about the good of humanity."

Instead of protesting Jakub agreed with his friends reproaches, and Dr. Skreta, feeling encouraged, went on: "Archimedes with his circles, Michelangelo with his block of stone, Pasteur with his test tubes-they and they alone have transformed human life and made real history, while the politicians…" Skreta paused and waved his hand scornfully.

"While the politicians?" asked Jakub, and went on: "I'll tell you. If science and art are in fact the proper, real arenas of history, politics on the contrary is the closed scientific laboratory where unprecedented experiments are conducted on mankind. There human guinea pigs are hurled through trap doors and then brought back onto the stage, tempted by applause and terrified by the gallows, denounced and forced to denounce. I worked in that lab as an assistant, but I also served there several times as a victim of vivisection. I know that I created nothing of value there (no more than those who worked with me did), but I probably came to understand better than others what man is."

"I understand you," said Bertlef, "and I too know that laboratory, even though I never worked as an assistant but always as a guinea pig. I was in Germany when the war broke out. The woman I was in love with at the time denounced me to the Gestapo. They had

come to her and shown her a photo of me in bed with another woman. She was hurt by it, and, as you know, love often takes on the features of hate. I went to prison with the strange sensation of having been led there by love. Is it not wonderful to find oneself in the hands of the Gestapo and to realize that this, in fact, is the privilege of a man who is loved too much?"

Jakub replied: "Something that always utterly disgusts me about mankind is seeing how its cruelty, its baseness, and its stupidity manage to wear the lyrical mask. She sends you to your death, and she experiences it as a romantic feat of wounded love. And you mount the scaffold because of an ordinary narrow-minded woman, feeling that you are playing a role in a tragedy Shakespeare wrote for you."

"After the war she came to me in tears," Bertlef went on, as though he had not heard Jakub's objection. "I told her: 'Don't worry, Bertlef is never vindictive.'"

"You know," said Jakub, "I often think about King Herod. You know the story. It's said that when he learned about the birth of the future king of the Jews, he was afraid he'd lose his throne, and he had all th

e newborns murdered. Personally I have a different view of Herod, even though I know it's only an imaginary game. To my mind Herod was an educated, wise, and very generous king, who had worked for a long time in the laboratory of politics and had learned much about life and mankind. He came to think that perhaps man should not have been created. His doubt, I might add, was not so uncalled-for and reprehensible. If I'm not

mistaken, even the Lord had doubts about mankind and thought of destroying this part of His work."

"Yes," Bertlef agreed, "it is in the sixth chapter of Genesis: 'I will destroy man whom I have created… for it repenteth me that I have made him.'"

"And perhaps it was only a moment of weakness on the Lord's part finally to have permitted Noah to take refuge in his ark in order to start afresh the history of man. Can we be sure that God never regretted this weakness? But whether He regretted it or not, there was nothing more to do. God can't make Himself ridiculous by constantly changing His decisions. But what if it was He who put the idea into Herod's head? Can that be ruled out?"

Bertlef shrugged his shoulders and said nothing.

"Herod was a king. He was not just responsible for himself alone. He couldn't tell himself, as I do: Let others do what they want, I refuse to procreate. Herod was a king and knew that he had to decide not only for himself but also for others, and he decided on behalf of all mankind that man would no longer reproduce. This is how the massacre of the newborns came about. His motives were not as vile as the ones tradition attributes to him. Herod was driven by a most generous wish finally to free the world from mankind's clutches."

"Your interpretation of Herod pleases me greatly," said Bertlef. "It pleases me so much that from now on I shall see the Massacre of the Innocents as you do. But don't forget that at the very moment Herod decided that mankind would cease to exist, there was born in

Bethlehem a little boy who was to elude the king's knife. And this child grew up and told people that only one thing was needed to make life worth living: to love one another. Herod was probably better educated and more experienced. Jesus was certainly wet behind the ears and did not know much about life. All his teachings might be explained by his youth and inexperience. By his naivete, if you wish. And yet he possessed the truth."

"The truth? Who has proved this truth?" Jakub asked sharply.

"No one," said Bertlef. "No one has proved it, and no one ever will prove it. Jesus loved his Father so much that he could not admit his Father's work was bad. He was not led to this conclusion by reason but by love. This is why only our hearts can bring the quarrel between Jesus and Herod to a close. Is it worth being a man, yes or no? I have no proof of it, but, along with Jesus, I believe the answer is yes." That said, he turned with a smile to Dr. Skreta: "That is why I sent my wife here to take the cure under the direction of Doctor Skreta, who to my mind is one of the holy disciples of Jesus, for he knows how to perform miracles and bring back to life women's dormant wombs. I drink to his health!"

10

Jakub had always treated Olga with paternal responsibility and playfully liked to call himself her "old gentleman." She knew, however, that he had many women with whom things were entirely different, and she envied them. But today, for the first time, she thought there was really something old about Jakub. In the way he behaved with her, she sensed the musti-ness that for the young emanates from the generation of their elders.

Old men are recognizable by their habit of bragging about past sufferings and making a museum of them (ah, these sad museums have so few visitors!). Olga realized that she was the most important living object in Jakub's museum and that Jakub's generously altruistic attitude toward her was meant to move visitors to tears.

Today too the most precious nonliving object in the museum had been revealed to her: the pale-blue tablet. Not long before, when he had unfolded in her presence the piece of paper the tablet was wrapped in, she had been surprised by not feeling the slightest emotion. Though she understood Jakub's contemplation of suicide in a bad time, she found the solemnity with which he let her know about it ridiculous. She found it ridiculous that he had unfolded the tissue paper so cautiously, as if the tablet were a precious diamond. And she didn't see why he wanted to give the poison back to

Dr. Skreta on the day of his departure, since he had maintained that every adult should under all circumstances be in control of his own death. If, once he was abroad, he were stricken by cancer, would he not need the poison? No, for Jakub the tablet was not simply poison, it was a symbolic prop he now wanted to return to the high priest in a religious service. It was enough to make you laugh.

She left the baths and headed toward the Richmond. Despite all her disillusioned reflections, she looked forward to seeing Jakub. She had a great desire to desecrate his museum, to function in it no longer as an object but as a woman. She was thus a bit disappointed to find a note on his door asking her to join him in the room next door, where he was waiting for her with Bertlef and Dr. Skreta. The thought of being in the company of others made her lose heart, all the more so since she didn't know Bertlef, and Dr. Skreta usually treated her with friendly but obvious indifference.

Bertlef quickly made her forget her shyness. He introduced himself with a deep bow and chided Dr. Skreta for not having acquainted him sooner with such an interesting woman.

Skreta responded that Jakub had asked him to look after the young woman, and he had deliberately refrained from introducing her to Bertlef because he knew that no woman could resist him.

Bertlef greeted this excuse with a satisfied smile. Then he picked up the telephone receiver to order dinner.

"It's incredible,'' said Dr. Skreta, "how our friend

manages to live affluently in this hole where there's not a single restaurant that serves a decent meal."

Bertlef dug his hand into an open cigar box, beside the telephone, which was filled with half-dollar pieces: "Avarice is a sin," he said, and smiled.

Jakub remarked that he had never before met anyone who believed so fervently in God while knowing so well how to enjoy life.

"That is probably because you have never before met a true Christian. The word of the Gospel, as you know, is a message of joy. The enjoyment of life is the most important teaching of Jesus."

Olga considered this an opportunity to enter the conversation: "Insofar as I can trust what my teachers said, Christians saw earthly life as a vale of tears and rejoiced in the idea that true life would begin for them after death."

"My dear young lady," Bertlef said, "never believe teachers."

"And what the saints all did," Olga went on, "was to renounce life. Instead of making love they flagellated themselves; instead of discussing things as you and I are doing they retreated to hermitages; and instead of ordering dinner by telephone they chewed roots."

"You don't understand anything about saints, my dear. These people were immensely attached to the pleasures of life. But they attained them by other means. In your opinion, what is man's supreme pleasure? You could try to guess, but you would be deceiving yourself, because you are not sincere enough. This

is not a reproach, for sincerity requires self-knowledge and self-knowledge is the fruit of age. How could a young woman like you, who radiates youthfulness, be sincere? She cannot be sincere because she does not even know what there is within her. But if she did know, she would, have to admit along with me that the greatest pleasure is to be admired. Do you agree?"

Olga replied that she knew of greater pleasures.

"No," said Bertlef. "Take for instance your famous runner, the one every child here knows about because he won three Olympic events. Do you think he renounced life? And yet instead of chatting, making love, and eating well, he surely had to spend his time constantly running round and round a stadium. His training very much resembled what our most celebrated saints did. Saint Makarios of Alexandria, when he was in the desert, regularly refilled a basket with sand, put it on his back, and traveled endless distances in this way day afte

r day until he dropped from total exhaustion. But both for your runner and for Saint Makarios, there was surely a great reward that amply repaid them for all their efforts. Do you know what it is to hear the applause in an immense Olympic stadium? There is no greater joy! Saint Makarios of Alexandria knew why he carried a basket of sand on his back. The glory of his desert marathons soon spread throughout Christendom. And Saint Makarios was like your runner. Your runner, too, first won the five-thousand-meter race, then the ten-thousand-meter, and finally nothing sufficed for him but to win the marathon as

well. The desire for admiration is insatiable. Saint Makarios went to a monastery in Thebes without making himself known and asked to be accepted as a member. Then, when the Lenten fast began, came his hour of glory. All the monks fasted sitting down, but he remained standing for the entire forty-day fast! You have no idea what a triumph that was! Or remember Saint Simeon Stylites! In the desert he built a pillar with a narrow platform on top. There was no room to sit on it, he had to stand. And he remained standing there for the rest of his life, and all Christendom enthusiastically admired this man's incredible record, which seemed to exceed human limits. Saint Simeon Stylites was the Gagarin of the fifth century. Can you imagine the happiness of Saint Genevieve of Paris the day she learned from a Welsh trading mission that Saint Simeon Stylites had heard of her and blessed her from atop his pillar? And why do you think he wanted to set a record? Because he didn't care about life and mankind? Don't be naive! The church fathers knew very well that Saint Simeon Stylites was vain, and they put him to the test. In the name of their spiritual authority they ordered him to descend from his pillar and retire from competition. It was a harsh blow to Saint Simeon Stylites! But he was either wise or cunning enough to obey them. The church fathers were not hostile to his record-setting, but they wanted to be certain that Saint Simeon's vanity did not prevail over his sense of discipline. As soon as they saw him sadly descending from his perch, they ordered him to climb back up,

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

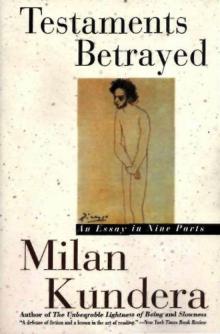

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts