- Home

- Milan Kundera

Symposium

Symposium Read online

Symposium

by Milan Kundera

from Laughable Loves

This translation 1999 Aaron Asher

ACT ONE

The Staff Room

The doctors' staff room (in any ward of any hospital in any town you like) has brought together five characters and intertwined their actions and speech into a trivial yet, for all that, most enjoyable story.

Dr. Havel and Nurse Elisabet are here (today both of them are on the night shift), and there are two additional doctors (a less than important pretext led them here, so that they could sit with the two who are on duty over a couple of bottles of wine): the bald chief physician of this ward and a comely thirty-year-old woman doctor from another ward, who the whole hospital knows are going with each other.

(The chief physician is, of course, married, and just a moment before he had uttered his favorite maxim, which should give evidence not only of his wit but also of his intentions: "My dear colleagues, as you know, the greatest misfortune for a man is a happy marriage; he hasn't the slightest hope of a divorce.")

In addition to these four there is still a fifth, but he is not actually here, because, as the youngest, he has just been sent for another bottle. And there is a window here, important because it's open and because through it from the darkness outside there enters into the room a warm, fragrant, and moonlit summer night. And finally, there is an agreeable mood here, manifesting itself in the appreciative chatter of all, especially, however, of the chief physician, who listens to his own adages with enamored ears.

A little later in the evening (and only here in fact does our story begin), certain tensions can be noted: Elisabet has drunk more than is advisable for a nurse on duty, and on top of that, begun to behave toward Havel with defiant flirtatiousness, which goes against the grain with him and provokes him to admonishing invective.

Havel's Admonition

"My dear Elisabet, I don't get you. Every day you rummage around in festering wounds, you jab old men in their wrinkled backsides, you give enemas, you take out bedpans. Your lot has provided you with the enviable opportunity to understand human corporeality in all its metaphysical vanity. But your vitality is incorrigible. It is impossible to shake your tenacious desire to be flesh and nothing but flesh. Your breasts know how to rub against a man standing five meters away from you. My head is already spinning from those eternal gyrations your untiring butt describes when you walk. Go to the devil, get away from me! Those boobs of yours are ubiquitous�like God! You should have given the injections ten minutes ago!"

Dr. Havel Is Like Death; He Takes Everything

When Nurse Elisabet (ostentatiously offended) had left the staff room, condemned to jab two very old backsides, the chief physician said: "I ask you, Havel, why do you insist on turning down poor Elisabet?"

Dr. Havel took a sip of wine and replied: "Chief, don't get mad at me for that. It's not because she isn't pretty and is getting on in years. Believe me, I've had women still uglier and far older."

"Yes, it's a well-known fact about you: you're like death; you take everything. But if you take everything, why don't you take Elisabet?"

"Maybe," said Havel, "it's because she shows her desire so conspicuously that it resembles an order. You say that I am like death in relation to women. But not even death likes to be given an order."

The Chief Physician's Greatest Success

"I think I understand you," the chief physician answered. "When I was some years younger, I knew a girl who went to bed with everyone, and because she was pretty I was determined to have her. And imagine, she turned me down. She went to bed with my colleagues, with the chauffeurs, with the boiler man, with the cook, even with the undertaker, only not with me. Can you imagine that?"

"Sure," said the woman doctor.

"Let me tell you," the chief physician said testily. "It was then a couple of years after graduation, and 1 was a big shot. I believed that every woman was attainable, and I had succeeded in proving this with relatively hard to get women. And look, I came to grief with this readily attainable girl."

"If I know you, you certainly must have a theory about it," said Dr. Havel.

"I do," replied the chief physician. "Eroticism is not only a desire for the body, but to an equal extent a desire for honor. The partner you've won, who cares about you and loves you, becomes your mirror, the measure of your importance and your merits. For my little tart this was a difficult task. When you go to bed with everyone you stop believing that such a commonplace thing as making love can still have any kind of importance. And so you seek the true erotic honor in the opposite. The only man who could provide that girl with a clear gauge of her worth was one who wanted her, but whom she herself had rejected. And because she understandably longed to verify to herself that she was the most beautiful and best of women, she went about choosing this one man, whom she would honor with her refusal, very strictly and captiously. When in the end she chose me, I understood that this was an exceptional honor, and to this day I consider this my greatest erotic success."

"It's quite marvelous the way you are able to turn water into wine," said the woman doctor.

"Does it offend you that I don't consider you my greatest success?" said the chief physician. "You must understand me. Though you are a virtuous woman, I am not, nevertheless (and you don't know how much this grieves me), your first and last, while for that tart I was. Believe me, she has never forgotten me, and to this day nostalgically remembers how she rejected me. I tell this story only to bring out the analogy to Havel's rejection of Elisabet."

In Praise of Freedom

"Good God, sir." Havel let out a groan. "I hope you're not saying that in Elisabet I'm seeking an image of my human worth!"

"Certainly not," said the woman doctor caustically.

"After all, you've already explained to us that Elisa-

bet's provocativeness strikes you as an order, and you

wish to retain the illusion that it is you who are choosing

the woman."

"You know, although we talk about it in those terms, Doctor, it isn't like that." Havel did a bit of thinking. "I was only trying to be witty when I said to you that Elisabet's provocativeness bothers me. To tell the truth, I've had women far more provocative than she, and their provocativeness suited me quite well, because it pleasantly speeded up the course of events."

"So why the hell don't you take Elisabet?" cried the chief physician.

"Chief, your question isn't as stupid as it seemed to me at first, because I see that as a matter of fact it's hard to answer. If I'm going to be frank, then I don't know why I don't take Elisabet. I've slept with women more hideous, more provocative, and older. From this it follows that I should necessarily sleep with her too. That's what the statisticians would say. All the cybernetic machines would draw the same conclusion. And you see, perhaps for those very reasons, I don't take her. Perhaps I want to resist necessity. To trip up causality. To throw off the dismal predictability of the world's course by means of the free will of caprice."

"But why did you pick Elisabet for this?" cried the chief physician.

"Just because it's groundless. If there had been a reason, it would have been possible to find it in advance, and it would have been possible to determine my action in advance. It's just because of this groundlessness that a tiny scrap of freedom is granted us, for which we must untiringly reach out, so that in this world of iron laws there should remain a little human disorder. My dear colleagues, long live freedom," said Havel, and sadly raised his tumbler in a toast.

Whither the Responsibility of Man Extends

At this moment a new bottle appeared in the room; it drew the attention of all the doctors present. The charming, lanky young man who was standing in the doorway with it

was the ward intern, Flajsman. He put the bottle (very slowly) on the table, searched (a long time) for the corkscrew, then (slowly) pushed the corkscrew into the cork, and (quite slowly) screwed it into the cork, which he then (thoughtfully) drew out. From these parentheses Flajsman's slowness is evident; however, it testified far more to his slothful self-love than to clumsiness; with self-love the young intern would gaze peacefully into his own heart, overlooking the insignificant details of the outside world.

Dr. Havel said: "All the stuff we've been chattering about here is nonsense. It isn't I who am rejecting Elis-abet, but she me. Unfortunately. Anyhow, she's crazy about Flajsman."

"About me?" Flajsman raised his head from the bottle, then with slow steps returned the corkscrew to its place, came back to the table, and poured wine into the tumblers.

"You're a fine one," said the chief physician, supporting Havel. "Everybody knows this except you. Since you appeared in our ward, it's been hard to put up with her. It's been like that for two months now."

Flajsman looked (for a long time) at the chief physician and said: "I really didn't know that." And then he added: "And anyway it doesn't interest me at all."

"And what about those gentlemanly speeches of yours? That quacking about respect for women?" Havel feigned severity. "Doesn't it interest you that you cause Elisabet pain?"

"I feel pity for women, and I could never knowingly hurt them," said Flajsman. "But what I bring about involuntarily doesn't interest me, because I'm not in a position to influence it, and so I'm not responsible for it.

Then Elisabet came into the room. She evidently considered that it would be better to forget the insult and behave as if nothing had happened; so she behaved extremely unnaturally. The chief physician pushed a chair up to the table for her and filled a tumbler: "Drink, Elisabet, and forget all the wrongs that have been done you."

"Sure." Elisabet threw him a big smile and emptied the glass.

And the chief physician turned once again to Flajsman: "If a man were responsible only for what he is aware of, blockheads would be absolved in advance from any guilt whatever. Only, my dear Flajsman, a man is obliged to know. A man is responsible for his ignorance. Ignorance is a fault. And that is why nothing absolves you from your guilt, and I declare that you are a boor in regard to women, even if you dispute it."

In Praise of Platonic Love

"I'm wondering if you've got that sublet for Miss Klara yet, you know, the one you promised her?" Havel laid into Flajsman, reminding him of his vain attempts to win the heart of a certain girl (known to all those present).

"No, I haven't, but I'm taking care of it." "It just happens that Flajsman behaves like a gentleman toward women. Our colleague Flajsman doesn't lead women by the nose," the woman doctor said, standing up for the intern.

"I can't bear cruelty toward women, because I have pity for them," the intern repeated.

"All the same Klara hasn't given herself to you," said Elisabet to Flajsman, and she started to laugh in a very improper way, so that the chief physician was once again forced to take the floor:

"She gave herself, she didn't give herself, it isn't nearly so important as you think, Elisabet. It is well known that Abelard was castrated, but that he and Heloise nonetheless remained faithfully in love. Their love was immortal. George Sand lived for seven years with Frederic Chopin, immaculate as a virgin, and there isn't a chance in a million that you could compete with them when it comes to love! I don't want to introduce into this sublime context the case of the girl who by rejecting me gave me the highest reward of love. But note this well, my dear Elisabet, love is connected far more loosely with what you so incessantly think about than it might seem. Surely you don't doubt that Klara loves Flajsman! She's nice to him, but nevertheless she rejects him. This sounds illogical to you, but love is precisely that which is illogical."

"What's illogical in that?" Elisabet once again laughed in an improper way. "Klara cares about the apartment. That's why she's nice to Flajsman: but she doesn't feel like sleeping with him, maybe because she's sleeping with someone else. But that guy can't get her an apartment."

At that moment Flajsman raised his head and said: "You're getting on my nerves. You're like an adolescent. What if shame restrains a woman? That wouldn't occur to you, would it? What if she has some disease she's hiding from me? A surgical scar that disfigures her? Women are capable of being terribly ashamed. But you, Elisabet, you know almost nothing about this."

"Or else," said the chief physician, coming to Flajsman's aid, "when Klara is face to face with Flajsman, she is so petrified by the anguish of love that she cannot make love with him. Elisabet, can't you imagine that you could love someone so terribly that just because of it you couldn't go to bed with him?"

Elisabet confessed that she couldn't imagine that.

The Signal

At this point we can stop following the conversation for a while (they go on uninterruptedly discussing trivia) and mention that all this time Flajsman has been trying to catch the woman doctor's eye, for he has found her terribly attractive since the time (it was about a month before) he first saw her. The sublimity of her thirty years dazzled him. Until now he'd known her only in passing, and today for the first time he had the opportunity of spending a longer time in the same room with her. It seemed to him that every now and then she returned his look, and this excited him.

After one such exchange of glances, the woman doctor got up for no reason at all, walked over to the window, and said, "It's gorgeous out. There's a full moon . . . ," and then she again reached out to Flajsman with a fleeting look.

Flajsman wasn't blind to such situations, and he at once grasped that it was a signal�a signal for him. He felt his chest swelling. His chest is a sensitive instrument, worthy of Stradivarius's workshop. From time to time he would feel the aforementioned swelling, and each time he was certain that this swelling had the inevitability of an omen announcing the advent of something great and unprecedented, something exceeding all his dreams.

This time he was partly stupefied by the swelling and partly (in the corner of his mind the stupor hadn't reached) amazed: How was it that his desire had such power that at its summons reality submissively hurried to come into being? Continuing to marvel at its power, he was on the lookout for the conversation to become more heated so that the arguers would forget about his presence. As soon as this happened, he slipped out of the room.

The Handsome Young Man with His Arms Folded

The ward where this impromptu symposium was taking place was on the ground floor of an attractive pavilion, situated (close to other pavilions) in the large hospital garden. Now Flajsman entered this garden. He leaned against the tall trunk of a plane tree, lit a cigarette, and gazed at the sky. It was summer, fragrances floated through the air, and a round moon was suspended in the black sky.

He tried to imagine the course of future events: The woman doctor who had indicated to him a little while before that he should step outside would bide her time until her baldpate was more involved in the conversation than in watching her, and then probably she would inconspicuously announce that a small, intimate need compelled her to absent herself from the company for a moment.

And what else would happen? He deliberately didn't want to imagine anything else. His swelling chest was apprising him of a love affair, and that was enough for him. He believed in his own good fortune, he believed in his star of love, and he believed in the woman doctor. Pampered by his self-assurance (a self-assurance that was always a bit amazed at itself), he lapsed into agreeable passivity. That is to say he always saw himself as an attractive, successful, well-loved man, and it gratified him to await a love affair with his arms folded, so to speak. He believed that precisely this posture was bound to provoke both women and fate.

Perhaps at this opportunity it is worth mentioning that Flajsman very often, if not uninterruptedly (and with self-love), saw himself; so he was continuously accompanied by a double and this made his solitude

quite amusing. This time he not only stood leaning against the plane tree smoking, but he simultaneously observed himself with self-love. He saw how he was standing (handsome and boyish) leaning against the plane tree, nonchalantly smoking. He diverted himself for some time with this sight, until finally he heard light footsteps coming in his direction from the pavilion. He purposely didn't turn around. He drew once more on his cigarette, exhaled the smoke, and looked at the sky. When the steps were quite close to him, he said in a tender, winning voice: "I knew that you would come."

Urination

"That wasn't so hard to figure out,'' the chief physician replied. "I always prefer to take a leak in nature rather than in modern facilities, which are foul. Here my little golden fountain will before long wondrously unite with the soil, the grass, the earth. For, Flajsman, I arose from the dust, and now at least in part I shall return to the dust. A leak in nature is a religious ceremony, by means of which we promise the earth that in the end we'll return to it entirely."

As Flajsman remained silent, the chief physician questioned him: "And what about you? Did you come to look at the moon?" And as Flajsman stubbornly continued to be silent the chief physician said: "You're a real lunatic, Flajsman. And that's why I like you so much." Flajsman perceived the chief physician's words as mockery, and wanting to keep his image, he said aloofly: "Let's leave the moon out of it. I came to take a piss too."

"My dear Flajsman," said the chief physician very gently, "from you I consider this an exceptional show of kindness toward your aging boss."

Then they both stood under the plane tree performing the act the chief physician with untiring rapture and in ever new images had described as a sacred rite.

ACT TWO

The Handsome and Sarcastic Young Man

Then they went back together down the long corridor, and the chief physician put his arm around the intern's shoulder in a brotherly fashion. The intern was certain that the jealous baldpate had detected the woman doctor's signal and was now mocking him with his friendly effusions! Of course he couldn't remove his boss's arm from his shoulder, but all the more did anger accumulate in his heart. And the only thing that consoled him was that not only was he full of anger, but also he immediately saw himself in this angry state, and was pleased with the furious young man who returned to the staff room and to everyone's surprise was suddenly an utterly different person: sarcastic, witty, almost demonic.

When they both actually entered the staff room, Elisabet was standing in the middle of the room, twisting about horribly from the waist and emitting some singing sounds in a low voice. Dr. Havel looked at the floor, and the woman doctor, so as to relieve the shock

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

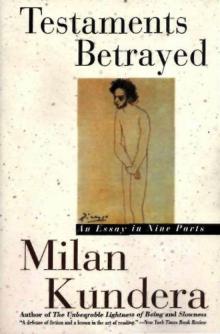

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts