- Home

- Milan Kundera

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Read online

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Milan Kundera

A novel of irreconcilable loves and infidelities, which embraces all aspects of human existence, and addresses the nature of twentieth-century 'Being'.

Milan Kundera

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

Translated from the Czech by Michael Henry Heim

© 1982

PART ONE . Lightness and Weight

1

The idea of eternal return is a mysterious one, and Nietzsche has often perplexed other philosophers with it: to think that everything recurs as we once experienced it, and that the recurrence itself recurs ad infinitum! What does this mad myth signify?

Putting it negatively, the myth of eternal return states that a life which disappears once and for all, which does not return, is like a shadow, without weight, dead in advance, and whether it was horrible, beautiful, or sublime, its horror, sublimity, and beauty mean nothing. We need take no more note of it than of a war between two African kingdoms in the fourteenth century, a war that altered nothing in the destiny of the world, even if a hundred thousand blacks perished in excruciating torment.

Will the war between two African kingdoms in the fourteenth century itself be altered if it recurs again and again, in eternal return?

It will: it will become a solid mass, permanently protuberant, its inanity irreparable.

If the French Revolution were to recur eternally, French historians would be less proud of Robespierre. But because they deal with something that will not return, the bloody years of the Revolution have turned into mere words, theories, and discussions, have become lighter than feathers, frightening no one. There is an infinite difference between a Robespierre who occurs only once in history and a Robespierre who eternally returns, chopping off French heads.

Let us therefore agree that the idea of eternal return implies a perspective from which things appear other than as we know them: they appear without the mitigating circumstance of their transitory nature. This mitigating circumstance prevents us from coming to a verdict. For how can we condemn something that is ephemeral, in transit? In the sunset of dissolution, everything is illuminated by the aura of nostalgia, even the guillotine.

Not long ago, I caught myself experiencing a most incredible sensation. Leafing through a book on Hitler, I was touched by some of his portraits: they reminded me of my childhood. I grew up during the war; several members of my family perished in Hitler's concentration camps; but what were their deaths compared with the memories of a lost period in my life, a period that would never return?

This reconciliation with Hitler reveals the profound moral perversity of a world that rests essentially on the nonexistence of return, for in this world everything is pardoned in advance and therefore everything cynically permitted.

2

If every second of our lives recurs an infinite number of times, we are nailed to eternity as Jesus Christ was nailed to the cross. It is a terrifying prospect. In the world of eternal return the weight of unbearable responsibility lies heavy on every move we make. That is why Nietzsche called the idea of eternal return the heaviest of burdens (das schwerste Gewicht).

If eternal return is the heaviest of burdens, then our lives can stand out against it in all their splendid lightness.

But is heaviness truly deplorable and lightness splendid?

The heaviest of burdens crushes us, we sink beneath it, it pins us to the ground. But in the love poetry of every age, the woman longs to be weighed down by the man's body. The heaviest of burdens is therefore simultaneously an image of life's most intense fulfillment. The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they become.

Conversely, the absolute absence of a burden causes man to be lighter than air, to soar into the heights, take leave of the earth and his earthly being, and become only half real, his movements as free as they are insignificant.

What then shall we choose? Weight or lightness?

Parmenides posed this very question in the sixth century before Christ. He saw the world divided into pairs of opposites:

light/darkness, fineness/coarseness, warmth/cold, being/non-being. One half of the opposition he called positive (light, fineness, warmth, being), the other negative. We might find this division into positive and negative poles childishly simple except for one difficulty: which one is positive, weight or lightness?

Parmenides responded: lightness is positive, weight negative.Was he correct or not? That is the question. The only certainty is: the lightness/weight opposition is the most mysterious, most ambiguous of all.

3

I have been thinking about Tomas for many years. But only in the light of these reflections did I see him clearly. I saw him standing at the window of his flat and looking across the courtyard at the opposite walls, not knowing what to do.

He had first met Tereza about three weeks earlier in a small Czech town. They had spent scarcely an hour together. She had accompanied him to the station and waited with him until he boarded the train. Ten days later she paid him a visit. They made love the day she arrived. That night she came down with a fever and stayed a whole week in his flat with the flu.

He had come to feel an inexplicable love for this all but complete stranger; she seemed a child to him, a child someone had put in a bulrush basket daubed with pitch and sent downstream for Tomas to fetch at the riverbank of his bed.

She stayed with him a week, until she was well again, then went back to her town, some hundred and twenty-five miles from Prague. And then came the time I have just spoken of and see as the key to his life: Standing by the window, he looked out over the courtyard at the walls opposite him and deliberated.

Should he call her back to Prague for good? He feared the responsibility. If he invited her to come, then come she would, and offer him up her life.

Or should he refrain from approaching her? Then she would remain a waitress in a hotel restaurant of a provincial town and he would never see her again.

Did he want her to come or did he not?

He looked out over the courtyard at the opposite walls, seeking an answer.

He kept recalling her lying on his bed; she reminded him of no one in his former life. She was neither mistress nor wife. She was a child whom he had taken from a bulrush basket that had been daubed with pitch and sent to the riverbank of his bed. She fell asleep. He knelt down next to her. Her feverous breath quickened and she gave out a weak moan. He pressed his face to hers and whispered calming words into her sleep. After a while he felt her breath return to normal and her face rise unconsciously to meet his. He smelled the delicate aroma of her fever and breathed it in, as if trying to glut himself with the intimacy of her body. And all at once he fancied she had been with him for many years and was dying. He had a sudden clear feeling that he would not survive her death. He would lie down beside her and want to die with her. He pressed his face into the pillow beside her head and kept it there for a long time.

Now he was standing at the window trying to call that moment to account. What could it have been if not love declaring itself to him?

But was it love? The feeling of wanting to die beside her was clearly exaggerated: he had seen her only once before in his life! Was it simply the hysteria of a man who, aware deep down of his inaptitude for love, felt the self-deluding need to simulate it? His unconscious was so cowardly that the best partner it could choose for its little comedy was this miserable provincial waitress with practically no chance at all to enter his life!

Looking out over the courtyard at the dirty walls, he realized he had no idea whether it was hysteria or love.

And he w

as distressed that in a situation where a real man would instantly have known how to act, he was vacillating and therefore depriving the most beautiful moments he had ever experienced (kneeling at her bed and thinking he would not survive her death) of their meaning.

He remained annoyed with himself until he realized that not knowing what he wanted was actually quite natural.

We can never know what to want, because, living only one life, we can neither compare it with our previous lives nor perfect it in our lives to come.

Was it better to be with Tereza or to remain alone?

There is no means of testing which decision is better, because there is no basis for comparison. We live everything as it comes, without warning, like an actor going on cold. And what can life be worth if the first rehearsal for life is life itself? That is why life is always like a sketch. No, sketch is not quite the word, because a sketch is an outline of something, the groundwork for a picture, whereas the sketch that is our life is a sketch for nothing, an outline with no picture.

Einmal ist keinmal, says Tomas to himself. What happens but once, says the German adage, might as well not have happened at all. If we have only one life to live,we might as well not have lived at all.

4

But then one day at the hospital, during a break between operations, a nurse called him to the telephone. He heard Tereza's voice coming from the receiver. She had phoned him from the railway station. He was overjoyed. Unfortunately, he had something on that evening and could not invite her to his place until the next day. The moment he hung up, he reproached himself for not telling her to go straight there. He had time enough to cancel his plans, after all! He tried to imagine what Tereza would do in Prague during the thirty-six long hours before they were to meet, and had half a mind to jump into his car and drive through the streets looking for her.

She arrived the next evening, a handbag dangling from her shoulder, looking more elegant than before. She had a thick book under her arm. It was Anna Karenina. She seemed in a good mood, even a little boisterous, and tried to make him think she had just happened to drop in, things had just worked out that way: she was in Prague on business, perhaps (at this point she became rather vague) to find a job.

Later, as they lay naked and spent side by side on the bed, he asked her where she was staying. It was night by then, and he offered to drive her there. Embarrassed, she answered that she still had to find a hotel and had left her suitcase at the station.

Only two days ago, he had feared that if he invited her to Prague she would offer him up her life. When she told him her suitcase was at the station, he immediately realized that the suitcase contained her life and that she had left it at the station only until she could offer it up to him.

The two of them got into his car, which was parked in front of the house, and drove to the station. There he claimed the suitcase (it was large and enormously heavy) and took it and her home.

How had he come to make such a sudden decision when for nearly a fortnight he had wavered so much that he could not even bring himself to send a postcard asking her how she was?

He himself was surprised. He had acted against his principles. Ten years earlier, when he had divorced his wife, he celebrated the event the way others celebrate a marriage. He understood he was not born to live side by side with any woman and could be fully himself only as a bachelor. He tried to design his life in such a way that no woman could move in with a suitcase. That was why his flat had only the one bed. Even though it was wide enough, Tomas would tell his mistresses that he was unable to fall asleep with anyone next to him, and drive them home after midnight. And so it was not the flu that kept him from sleeping with Tereza on her first visit. The first night he had slept in his large armchair, and the rest of that week he drove each night to the hospital, where he had a cot in his office.

But this time he fell asleep by her side. When he woke up the next morning, he found Tereza, who was still asleep, holding his hand. Could they have been hand in hand all night? It was hard to believe.

And while she breathed the deep breath of sleep and held his hand (firmly: he was unable to disengage it from her grip), the enormously heavy suitcase stood by the bed.

He refrained from loosening his hand from her grip for fear of waking her, and turned carefully on his side to observe her better.

Again it occurred to him that Tereza was a child put in a pitch-daubed bulrush basket and sent downstream. He couldn't very well let a basket with a child in it float down a stormy river! If the Pharaoh's daughter hadn't snatched the basket carrying little Moses from the waves, there would have been no Old Testament, no civilization as we now know it! How many ancient myths begin with the rescue of an abandoned child! If Polybus hadn't taken in the young Oedipus, Sophocles wouldn't have written his most beautiful tragedy!

Tomas did not realize at the time that metaphors are dangerous. Metaphors are not to be trifled with. A single metaphor can give birth to love.

5

He lived a scant two years with his wife, and they had a son. At the divorce proceedings, the judge awarded the infant to its mother and ordered Tomas to pay a third of his salary for its support. He also granted him the right to visit the boy every other week.

But each time Tomas was supposed to see him, the boy's mother found an excuse to keep him away. He soon realized that bringing them expensive gifts would make things a good deal easier, that he was expected to bribe the mother for the son's love. He saw a future of quixotic attempts to inculcate his views in the boy, views opposed in every way to the mother's. The very thought of it exhausted him. When, one Sunday, the boy's mother again canceled a scheduled visit, Tomas decided on the spur of the moment never to see him again.

Why should he feel more for that child, to whom he was bound by nothing but a single improvident night, than for any other? He would be scrupulous about paying support; he just didn't want anybody making him fight for his son in the name of paternal sentiments!

Needless to say, he found no sympathizers. His own parents condemned him roundly: if Tomas refused to take an interest in his son, then they, Tomas's parents, would no longer take an interest in theirs. They made a great show of maintaining good relations with their daughter-in-law and trumpeted their exemplary stance and sense of justice.

Thus in practically no time he managed to rid himself of wife, son, mother, and father. The only thing they bequeathed to him was a fear of women. Tomas desired but feared them. Needing to create a compromise between fear and desire, he devised what he called erotic friendship. He would tell his mistresses: the only relationship that can make both partners happy is one in which sentimentality has no place and neither partner makes any claim on the life and freedom of the other.

To ensure that erotic friendship never grew into the aggression of love, he would meet each of his long-term mistresses only at intervals. He considered this method flawless and propagated it among his friends: The important thing is to abide by the rule of threes. Either you see a woman three times in quick succession and then never again, or you maintain relations over the years but make sure that the rendezvous are at least three weeks apart.

The rule of threes enabled Tomas to keep intact his liaisons with some women while continuing to engage in short-term affairs with many others. He was not always understood. The woman who understood him best was Sabina. She was a painter. The reason I like you, she would say to him, is you're the complete opposite of kitsch. In the kingdom of kitsch you would be a monster.

It was Sabina he turned to when he needed to find a job for Tereza in Prague. Following the unwritten rules of erotic friendship, Sabina promised to do everything in her power, and before long she had in fact located a place for Tereza in the darkroom of an illustrated weekly. Although her new job did not require any particular qualifications, it raised her status from waitress to member of the press. When Sabina herself introduced Tereza to everyone on the weekly, Tomas knew he had never had a better friend as a mistress th

an Sabina.

6

The unwritten contract of erotic friendship stipulated that Tomas should exclude all love from his life. The moment he violated that clause of the contract, his other mistresses would assume inferior status and become ripe for insurrection.

Accordingly, he rented a room for Tereza and her heavy suitcase. He wanted to be able to watch over her, protect her, enjoy her presence, but felt no need to change his way of life. He did not want word to get out that Tereza was sleeping at his place: spending the night together was the corpus delicti of love.

He never spent the night with the others. It was easy enough if he was at their place: he could leave whenever he pleased. It was worse when they were at his and he had to explain that come midnight he would have to drive them home because he was an insomniac and found it impossible to fall asleep in close proximity to another person. Though it was not far from the truth, he never dared tell them the whole truth:

after making love he had an uncontrollable craving to be by himself; waking in the middle of the night at the side of an alien body was distasteful to him, rising in the morning with an intruder repellent; he had no desire to be overheard brushing his teeth in the bathroom, nor was he enticed by the thought of an intimate breakfast.

That is why he was so surprised to wake up and find Tereza squeezing his hand tightly. Lying there looking at her, he could not quite understand what had happened. But as he ran through the previous few hours in his mind, he began to sense an aura of hitherto unknown happiness emanating from them.

From that time on they both looked forward to sleeping together. I might even say that the goal of their lovemaking was not so much pleasure as the sleep that followed it. She especially was affected. Whenever she stayed overnight in her rented room (which quickly became only an alibi for Tomas), she was unable to fall asleep; in his arms she would fall asleep no matter how wrought up she might have been. He would whisper impromptu fairy tales about her, or gibberish, words he repeated monotonously, words soothing or comical, which turned into vague visions lulling her through the first dreams of the night. He had complete control over her sleep: she dozed off at the second he chose.

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

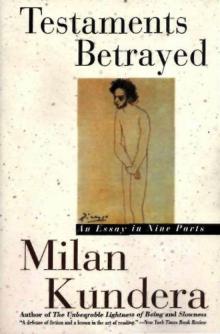

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts