- Home

- Milan Kundera

Farewell Waltz Page 6

Farewell Waltz Read online

Page 6

"Did that hurt?"

"No," said the patient.

"I also came here to give you back the tablet."

Dr. Skreta barely took notice of Jakub's words. He was still busy with his patient. He inspected her from head to toe with a serious and thoughtful expression and said: "In your case, it would really be a shame if you didn't have a child. You've got long legs, a well-developed pelvis, a beautiful rib cage, and quite a pleasant face."

He touched the patient's face, chucked her chin, and said: "A nice jaw, sturdy and well-shaped."

Then he took hold of her thigh: "And you've got marvelously firm bones. It looks like they're shining under your muscles."

He went on for a time praising the patient while manipulating her body, and she didn't protest or giggle

any longer, for the seriousness of the physician's interest in her put his touchings well on this side of shame-lessness.

At last he indicated that she should get dressed, and he turned to his friend: "What were you saying?"

"That I came to give you back the tablet."

"What tablet?"

As she was dressing the woman said: "Well, Doctor, do you think there's any hope for me?"

"I'm extremely satisfied," said Dr. Skreta. "I think that things are developing positively and that we, you and I both, can count on a success."

Thanking him, the woman left the examining room, and then Jakub said: "Years ago you gave me a tablet nobody else would give me. Now that I'm leaving, I think I won't need it anymore, and I should give it back to you."

"Keep it! The tablet could be just as useful elsewhere as it is here."

"No, no. The tablet was part of this country. I want to leave in this country everything that belongs to it," said Jakub.

"Doctor, I'm going to bring in the next one," said the nurse.

"Send all those females home," said Dr. Skreta. "I've done my work for today. You'll see, that last one will surely have a child. That's enough for a day, no?"

The nurse looked at the doctor tenderly and yet showed not the slightest intention of obeying him.

Dr. Skreta understood this look: "All right, don't

send them away; just tell them I'll be back in half an hour."

"Doctor, you said half an hour yesterday too, and I had to run after you in the street."

"Don't worry, my dear, I'll be back in half an hour," said Skreta, and he motioned his friend to return the white coat to the nurse. Then they left the building and went straight across the park to the Richmond.

2

They went up to the second floor and followed the long red carpet to the end of the corridor. Dr. Skreta opened a door and with his friend entered a cramped but pleasant room.

"It's nice of you," said Jakub, "always to have a room for me here."

"I've got some rooms set aside now at this end of the corridor for my special patients. Next to your room is a beautiful corner suite where cabinet ministers and industrialists stayed in the old days. I've put up my prize patient there, a rich American whose family originated here. He's become something of a friend."

"And where does Olga live?"

"In Marx House, like me. Don't worry, she's all right there."

"The main thing is that you're looking after her. How is she doing?"

"She has the usual problems of women with fragile nerves."

"I told you in my letter about the life she's had."

"Most women come here to gain fertility. In your ward's case, it would be better if she didn't take advantage of her fertility. Have you ever seen her naked?"

"My God! Certainly not!" said Jakub.

"Well, take a look at her! She has tiny breasts hanging from her chest like two little plums. You can see her ribs. From now on look more closely at rib cages. A real thorax should be aggressive, outgoing, it has to expand as if it wants to take up as much space as possible. On the other hand, there are rib cages that are on the defensive, that retreat from the outside world; it's like a straitjacket getting tighter and tighter around someone and finally suffocating him. That's the case with hers. Tell her to show it to you."

"It's the last thing I'd do," said Jakub.

"You're afraid that if you saw it you'd no longer regard her as your ward."

"On the contrary," said Jakub. "I'm afraid of feeling even more sorry for her."

"Incidentally, old friend," said Skreta, "that American is really an extremely odd type."

"Where can I see her right now?" asked Jakub.

"Who?"

"Olga."

"You can't see her now. She's having her treatment.

She has to spend the whole morning in the pool."

"I don't want to miss her. Can I phone her?"

Dr. Skreta lifted the receiver and dialed a number without interrupting his conversation with his friend: "I'm going to introduce you, and I want you to study him thoroughly for me. You're psychologically astute. You're going to see right through him. I've got plans for him."

"Like what?" asked Jakub, but Dr. Skreta was already talking into the receiver: "Is this Ruzena? How are you?… Don't worry, nausea is normal in your condition. I wanted to ask you if a patient of mine is in the pool right now, your neighbor in the room next door… Yes? Good, tell her she's got a visitor from the capital, above all tell her not to go anywhere… Yes, he'll be waiting for her at noon in front of the thermal building."

Skreta hung up. "Well, you heard that. You're going to see her again at noon. Damn, what were we just talking about?"

"About the American."

"Yes," said Skreta. "He's an extremely odd type. I cured his wife. They'd been unable to have children."

"And what's he here for?"

"His heart."

"You said you've got plans for him."

"It's humiliating," said Skreta indignantly, "what a physician is forced to do in this country in order to make a decent living! Klima, the famous trumpeter, is coming here. I have to accompany him on the drums!"

Jakub didn't think Skreta was being serious, but he pretended to be surprised: "What, you play the drums?"

"Yes, my friend! What can I do, now that I'm going to have a family?"

"What?" Jakub exclaimed, this time truly surprised. "A family? Are you telling me you're married?"

"Yes," said Skreta. "To Suzy?"

Suzy was a doctor at the spa who had been Skreta's girlfriend for years, but at the last moment he had always succeeded in avoiding marriage.

"Yes, to Suzy," said Skreta. "You know that every Sunday I used to climb up to the scenic view with her."

"So you're really married," said Jakub with melancholy.

"Every time we climbed up there," Skreta went on, "Suzy tried to convince me we should get married. And I'd be so worn out by the climb that I felt old and that there was nothing left for me but to marry. But in the end I always controlled myself, and when we came back down from the scenic view my strength would come back and I'd no longer want to get married. But one day Suzy made us take a detour, and the climb took so long I agreed to get married even before we got to the top. And now we're expecting a child, and I have to think a bit about money. The American also paints religious pictures. One could make a lot of money from that. What do you think?"

"Do you believe there's a market for religious pictures?"

"A fantastic market! All it takes, old friend, is to put up a stand next to the church on pilgrimage days and, at a hundred crowns apiece, we'd make a fortune! I could sell them for him and we'd split fifty-fifty."

"And what does he say?"

"The fellow has so much money he doesn't know what to do with it, and I'm sure I wouldn't be able to get him to go into business with me," said Skreta with a curse.

3

Olga clearly saw Nurse Ruzena waving to her from the edge of the pool, but she went on swimming and pretended she had not seen her.

The two women didn't like each other. Dr. Skreta had put Olga in a small room next to Ruzena'

s. Ruzena was in the habit of playing the radio very loud, and Olga liked quiet. She had rapped on the wall at various times, and the nurse's only response was to turn up the volume.

Ruzena persisted in waving and finally succeeded in telling the patient that a visitor from the capital would be meeting her at noon.

Olga realized that it was Jakub, and she felt immense joy. And instantly she was surprised by this joy: How

can I be feeling such pleasure at the idea of seeing him again?

Olga was actually one of those modern women who readily divide themselves into a person who lives life and a person who observes it.

But even the Olga who observed life was rejoicing. For she understood very well that it was utterly excessive for Olga (the one who lived life) to rejoice so impetuously, and because she (the one who observed life) was mischievous this excessiveness gave her pleasure. She smiled at the idea that Jakub would be frightened if he knew of the fierceness of her joy.

The hands of the clock above the pool showed a quarter to twelve. Olga wondered how Jakub would react if she were to throw her arms around his neck and kiss him passionately. She swam to the edge of the pool, climbed out, and went to a cubicle to change. She regretted a little not having been informed of Jakub's visit earlier in the day. She would have been better dressed. Now she was wearing an uninteresting little gray suit that spoiled her good mood.

There were times, such as a few minutes earlier while swimming in the pool, when she totally forgot her appearance. But now she was planted in front of the cubicle's small mirror and seeing herself in a gray suit. A few minutes earlier she had smiled mischievously at the idea that she could throw her arms around Jakub's neck and kiss him passionately. But she had that idea in the pool, where she had been swimming bodilessly, like a disembodied thought. Now that she had sud-

denly been provided with a body and a suit, she was far away from that joyous fantasy, and she knew that she was exactly what to her great anger Jakub always saw her as: a touching little girl who needed help.

If Olga had been a little more foolish, she would have found herself quite pretty. But since she was an intelligent girl, she considered herself much uglier than she really was, for she was actually neither ugly nor pretty, and any man with normal aesthetic requirements would gladly spend the night with her.

But since Olga delighted in dividing herself in two, the one who observed life now interrupted the one who lived life: What did it matter that she was like this or like that? Why suffer over a reflection in a mirror? Wasn't she something other than an object for men's eyes? Other than merchandise putting herself on the market? Was she incapable of being independent of her appearance, at the very least to the degree that any man can be?

She left the thermal building and saw a good-natured and touching face. She knew that instead of extending his hand to her he was going to pat her on the head like a good little girl. Sure enough, that is what he did.

"Where are we having lunch?" he asked.

She suggested the patients' dining room, where there was a vacant place at her table.

The patients' dining room was immense, filled with tables and people squeezed closely together having lunch. Jakub and Olga sat down and then waited a long

time before a waitress served them soup. Two other people were sitting at their table, and they tried to engage in conversation with Jakub, whom they immediately classified as a member of the sociable family of patients. It was therefore only in snatches during the general talk at the table that Jakub could question Olga about a few practical details: Was she satisfied with the food here, was she satisfied with the doctor, was she satisfied with the treatment? When he asked about her lodgings, she answered that she had a dreadful neighbor. She motioned with her head to a nearby table, where Ruzena was having lunch.

Their table companions took their leave, and looking at Ruzena, Jakub said: "Hegel has a curious reflection on the Grecian profile, whose beauty, according to him, comes from the fact that the nose and the brow form a single line that highlights the upper part of the head, the seat of intelligence and of the mind. Looking at your neighbor, I notice that her whole face, on the other hand, is concentrated on the mouth. Look how intensely she chews, and how she's talking loudly at the same time. Hegel would be disgusted by such importance being attached to the lower part, the animal part, of the face, and yet this girl I dislike is quite pretty."

"Do you think so?" asked Olga, her voice betraying annoyance.

That is why Jakub hastened to say: "At any rate I'd be afraid of being ground up into tiny bits by that ruminant's mouth." And he added: "Hegel would be more satisfied with you. The dominant part of your

face is the brow, which instantly tells everyone about your intelligence."

"Logic like that infuriates me," said Olga sharply. "It tries to show that a human being's physiognomy is imprinted on his soul. It's absolute nonsense. I picture my soul with a strong chin and sensual lips, but my chin is small and so is my mouth. If I'd never seen myself in a mirror and had to describe my outside appearance from what I know of the inside of me, the portrait wouldn't look at all like me! I am not at all the person I look like!"

4

It is difficult to find a word to characterize Jakub's relation to Olga. She was the daughter of a friend of his who had been executed when Olga was seven years old. Jakub decided at that time to take the little orphan under his wing. He had no children, and such obligation-free fatherhood appealed to him. He playfully called Olga his ward.

They were now in Olga's room. She plugged in a hotplate and put a small saucepan of water on it, and Jakub realized that he could not bring himself to reveal the purpose of his visit to her. He didn't dare tell her that he had come to say goodbye, was afraid the news

would take on too pathetic a dimension and generate an emotional climate between them that he regarded as uncalled for. He had long suspected her of being secretly in love with him.

Olga took two cups out of the cupboard, spooned instant coffee into them, and poured boiling water. Jakub stirred in a sugar cube and heard Olga say: "Please tell me, Jakub, what kind of man was my father really?" "Why do you ask?"

"Did he really have nothing to blame himself for?"

"What are you thinking of?" asked Jakub, amazed. Olga's father had been officially rehabilitated sometime earlier, and this political figure who had been sentenced to death and executed had been publicly proclaimed innocent. No one doubted his innocence.

"That's not what I mean," said Olga. "I mean just the opposite."

"I don't understand," said Jakub.

"I was wondering if he hadn't done to others exactly what was done to him. There wasn't a grain of difference between him and those who sent him to the gallows. They had the same beliefs, they were the same fanatics. They were convinced that even the slightest differences could put the revolution in mortal danger, and they suspected everyone. They sent him to his death in the name of holy things he himself believed in. Why then couldn't he have behaved toward others the same way they behaved toward him?"

"Time flies terribly fast, and the past is becoming

more and more incomprehensible," said Jakub after a moment's hesitation. "What do you know of your father besides a few letters, a few pages of his diary they kindly returned to you, and a few recollections from his friends?"

But Olga insisted: "Why are you so evasive? I asked you a perfectly clear question. Was my father like the ones who sent him to his death?"

"It's possible," said Jakub with a shrug.

"Then why couldn't he too have been capable of committing the same cruelties?"

"Theoretically," replied Jakub very slowly, "theoretically he was capable of doing to others exactly the same thing they did to him. There isn't a man in this world who isn't capable, with a relatively light heart, of sending a fellow human to his death. At any rate I've never met one. If men one day come to change in this regard, they'll lose a basic human attribute. They'll no longe

r be men but creatures of another species."

"You people are wonderful!" Olga exclaimed as if shouting at thousands of Jakubs. "When you turn everybody into murderers your own murders stop being crimes and just become an inevitable human attribute."

"Most people move around inside an idyllic circle between their home and their work," said Jakub. "They live in a secure territory beyond good and evil. They're sincerely appalled by the sight of a murderer. But taking them out of this secure territory is enough to make them murderers themselves, without their know-

ing how it happened. There are tests and temptations that only rarely turn up during the course of history. Nobody can resist them. But it's utterly useless to talk about this. What counts for you isn't what your father was theoretically capable of doing, because there's no way of proving it anyway. The only thing that should interest you is what he actually did or didn't do. And in that sense he had a clear conscience."

"Are you absolutely sure?"

"Absolutely. No one knew him better than I did."

"I'm really glad to hear this from you," said Olga. "Because I didn't ask you the question by chance. For a while now I've been getting anonymous letters. They say I'm wrong to play the daughter of a martyr, because my father, before he was executed, himself sent to prison innocent people whose only offense was to have an idea of the world different from his."

"Nonsense," said Jakub.

"These letters describe him as a relentless fanatic and cruel man. Of course they're spiteful anonymous letters, but they're not the letters of a primitive. They're not exaggerated, they're concrete and precise, and I almost ended up believing them."

"It's always the same kind of revenge," said Jakub. "I'm going to tell you something. When they arrested your father, the prisons were full of people the revolution had sent there in the first wave of terror. The prisoners recognized him as a well-known Communist, and at the first chance they pounced on him and beat him unconscious. The guards watched, smiling sadistically."

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

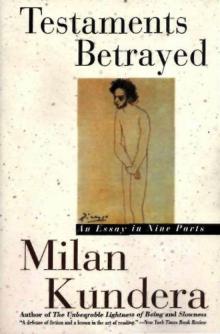

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts