- Home

- Milan Kundera

Immortality Page 2

Immortality Read online

Page 2

Agnes thought to herself: the Creator loaded a detailed program into the computer and went away. That God created the world and then left it to a forsaken humanity trying to address him in an echoless void— this idea isn't new. Yet it is one thing to be abandoned by the God of our forefathers and another to be abandoned by God the inventor of a cosmic computer. In his place, there is a program that is ceaselessly running in his absence, without anyone being able to change anything whatever. To load a program into the computer: this does not mean that the future has been planned down to the last detail, that everything is written "up above." For example, the program did not specify that in 1815 a battle would be fought near Waterloo and that the French would be defeated, but only that man is aggressive by nature, that he is condemned to wage war, and that technical progress would make war more and more terrible. Everything else is without importance, from the Creator's point of view, and is only a play of permutations and combinations within a general program, which is not a prophetic

MILAN KUNDERA

anticipation of the future but merely sets the limits of possibilities within which all power of decision has been left to chance.

That was the same with the project we call mankind. The computer did not plan an Agnes or a Paul, but only a prototype known as a human being, giving rise to a large number of specimens that are based on the original model and haven't any individual essence. Just like a Renault car, its essence is deposited outside, in the archives of the central engineering office. Individual cars differ only in their serial numbers. The serial number of a human specimen is the face, that accidental and unrepeatable combination of features. It reflects neither character nor soul, nor what we call the self. The face is only the serial number of a specimen.

Agnes recalled the newcomer who had just declared that she hated hot showers. She came in order to inform all the women present that (i) she likes saunas to be hot (2) she adores pride (3) she can't bear modesty (4) she loves cold showers (5) she hates hot showers. With these five strokes she had drawn her self-portrait, with these five points she defined her self and presented that self to everyone. And she didn't present it modestly (she said, after all, that she hated modesty!) but belligerently. She used passionate verbs such as "adore" and "detest," as if she wished to proclaim her readiness to fight for every one of those five strokes, for every one of those five points.

Why all this passion? Agnes asked herself, and she thought: When we are thrust out into the world just as we are, we first have to identify with that particular throw of the dice, with that accident organized by the divine computer: to get over our surprise that precisely this (what we see facing us in the mirror) is our self. Without the faith that our face expresses our self, without that basic illusion, that archillusion, we cannot live, or at least we cannot take life seriously. And it isn't enough for us to identify with our selves, it is necessary to do so passionately, to the point of life and death. Because only in this way can we regard ourselves not merely as a variant of a human prototype but as a being with its own irreplaceable essence. That's the reason the newcomer needed not only to draw her self-portrait but also to make it clear to all that it embodied something unique and irreplaceable, something worth fighting or even dying for.

Immortality

After spending a quarter of an hour in the heat of the sauna, Agnes rose and took a dip in a small pool filled with ice-cold water. Then she lay down to rest in the lounge, surrounded by other women who even here never stopped talking.

She wondered what kind of existence the computer had programmed for life after death.

Two possibilities came to mind. If the computer's field of activity is limited to our planet, and if our fate depends on it alone, then we cannot count on anything after death except some permutation of what we have already experienced in life; we shall again encounter similar landscapes and beings. Shall we be alone or in a crowd? Alas, solitude is not very likely; there is so little of it in life, so what can we expect after death! After all, the dead far outnumber the living! At best, existence after death would resemble the interlude she was now experiencing while reclining in a deck chair: from all sides she would hear the continuous babble of female voices. Eternity as the sound of endless babble: one could of course imagine worse things, but the idea of hearing women's voices forever, continuously, without end, gave her sufficient incentive to cling furiously to life and to do everything in her power to keep death as far away as possible.

But there is a second possibility, beyond our planet's computer there may be others that are its superiors. Then, indeed, existence will not need to resemble our past life and a person can die with a vague yet justified hope. And Agnes imagined a scene that had lately been often on her mind: a stranger comes to visit her. Likable, cordial, he sits down in a chair facing her husband and herself and proceeds to converse with them. Under the magic of the peculiar kindliness radiating from the visitor, Paul is in a good mood, chatty, intimate, and fetches an album of family photographs. The guest turns the pages and is perplexed by some of the photos. For example, one of them shows Agnes and Brigitte standing under the Eiffel Tower, and the visitor asks, "What is that?"

"That's Agnes, of course," Paul replies. "And this is our daughter, Brigitte!"

"I know that," says the guest. "I'm asking about this structure."

Paul looks at him in surprise: "Why, that's the Eiffel Tower!"

MILAN KUNDERA

"Oh, that's the Eiffel Tower," and he says it in the same tone of voice as if you had shown him a portrait of Grandpa and he had said, "So that's your grandfather I've heard so much about. I am glad to see him at last."

Paul is disconcerted, Agnes much less so. She knows who the man is. She knows why he came and what he was going to ask them about. That's why she is a bit nervous; she would like to be alone with him, without Paul, and she doesn't quite know how to arrange it.

4

AGNES's father had died five years ago. She had lost Mother a year before that. Even then Father had already been ill and everyone had expected his death. Mother, on the contrary, was still quite well, full of life; she seemed destined for a contented, prolonged widowhood, so Father was almost embarrassed when it was she, not he, who suddenly died. As if he were afraid that people would reproach him. "People" meaning Mother's family. His own relatives were scat- , tered all over the world, and except for a distant cousin living in Germany, Agnes had never met any of them. Mother's people, on the other hand, all lived in the same town: sisters, brothers, cousins, and a lot of nephews and nieces. Mother's father was a farmer from the mountains who had sacrificed himself for his children; he had made it possible for all of them to have a good education and to marry comfortably.

When Mother married Father, she was undoubtedly in love with him, which is not surprising, for he was a good-looking man and at thirty already a university professor, a respected occupation at that time. It pleased her to have such an enviable husband, but she derived even greater pleasure from having been able to bestow him as a gift upon her family, to which she was closely tied by the traditions of country life. But because Agnes's father was unsociable and taciturn (nobody knew whether it was because of shyness or because his mind was on other things, and thus whether his silence expressed modesty or lack of interest), Mother's gift made die family embarrassed rather than happy.

As time passed and both grew older, Mother was drawn to her family more and more; for one thing, while Father was eternally

MILAN KUNDERA

locked up in his study she had a hunger for talking, so that she spent long hours on the phone to sisters, brothers, cousins, and nieces and took an increasing interest in their problems. When she thought about it now, it seemed to Agnes that Mother's life was a circle: she had stepped out of her milieu, courageously coped with an entirely different world, and then began to return: she lived with her husband and two daughters in a garden villa and several times a year (at Christmas, for birthdays) invited all her rela

tives to great family celebrations; she imagined that after Father's death (which had been expected for so long that everyone regarded him indulgently as a person whose officially scheduled period of stay had expired) her sister and niece would move in to join her.

But then Mother died, and Father remained. When Agnes and her sister, Laura, came to visit him two weeks after the funeral, they found him sitting at the table with a pile of torn photographs. Laura picked them up and then began to shout, "Why have you torn up Mother's pictures?"

Agnes, too, leaned over the table to examine the debris: no, they weren't exclusively photos of Mother; the majority were actually of him alone, and only a few showed the two of them together or Mother alone. Confronted by his daughters, Father kept silent and offered no explanation. Agnes hissed at her sister, "Stop shouting at Dad!" But Laura kept on shouting. Father rose to his feet, went into the next room, and the sisters quarreled as never before. The next day Laura left for Paris and Agnes stayed behind. It was only then that Father told her he had found a small apartment in town and planned to sell the villa. That was another surprise. Everyone considered Father an ineffectual person who had handed over the reins of practical life to Mother. They all thought that he couldn't live without Mother, not only because he was incapable of taking care of anything himself but also because he didn't even know what he wanted, having long ago ceded her his own will. But when he decided to move out, suddenly, without the least hesitation, a few days after Mother's death, Agnes understood that he was putting into effect something he had been planning for a long time, and, therefore, that he knew perfectly well what he wanted. This

Immortality

was all the more intriguing, since he could have had no idea that he would survive Mother and therefore must have regarded the small apartment in town as a dream rather than a realistic project. He had lived with Mother in their villa, he had strolled with her in the garden, had hosted her sisters and cousins, had pretended to listen to their conversations, and all the time his mind was elsewhere, in a bachelor apartment; after Mother's death he merely moved to the place where he had long been living in spirit.

It was then that he first appeared to Agnes as a mystery. Why had he torn up the photos? Why had he been dreaming for so long about a bachelor apartment? And why had he not honored Mother's wish to have her sister and niece move into the villa? After all, that would have been more practical: they would surely have taken better care of him in his illness than some nurse who would have to be hired sooner or later. When she asked the reason for his move, he gave her a very simple answer: "What would a single person do with himself in such a large house?" She couldn't very well suggest that he take in Mother's sister and her daughter, for it was quite clear that he didn't want to do that. And so it occurred to her that Father, too, was returning full circle to his beginnings. Mother: from family through marriage back to family. He: from solitude through marriage back to solitude.

It was several years before Mother's death that he first became seriously ill. At that time Agnes took two weeks off from work to be with him. But she did not succeed in having him all to herself, because Mother did not leave them alone for a single moment. Once, two of Father's colleagues from the university came to visit him. They asked him a lot of questions, but Mother answered them. Agnes lost her patience: "Please, Mother, let Father speak for himself!" Mother was offended: "Can't you see that he is sick!" Toward the end of those two weeks his condition improved slightly, and finally Agnes twice managed to go out alone with him for a walk. But the third time Mother went along with them again.

A year after Mother's death his illness took a sharp turn for the worse. Agnes went to see him, stayed with him for three days, and on the morning of the fourth day he died. It was only during those last

MILAN KUNDERA

three days that she succeeded in being with him as she had always dreamed. She had told herself that they were fond of each other but could never really get to know each other because they had never had an opportunity to be alone. The only time they even came close was between her eighth and twelfth years, when Mother had to devote herself to little Laura. During that time they often took long walks together in the countryside and he answered many of her questions. It was then that he spoke of the Creator's computer and of many other things. All that she remembered of those conversations were simple statements, like fragments of valuable pottery that now as an adult she tried to put back together.

His death ended the pair's sweet three-day solitude. The funeral was attended by all of Mother's relatives. But because Mother herself was not there, there was nobody to arrange a wake and everyone quickly dispersed. Besides, the fact that Father had sold the house and had moved into a bachelor apartment was taken by relatives as a gesture of rejection. Now they thought only of the wealth awaiting both daughters, for the villa must have fetched a high price. They learned from the notary, however, that Father had left everything to the society of mathematicians he had helped to found. And so he became even more of a stranger to them than he had been when he was alive. It was as if through his will he had wanted to tell them to kindly forget him.

Shortly after his death, Agnes noticed that her bank balance had grown by a sizable amount. She now understood everything. Her seemingly impractical father had actually acted very cleverly. Ten years earlier, when his life was first threatened, she had come to visit him for two weeks, and he had persuaded her to open a Swiss bank account. Shortly before his death he had transferred practically all his money to this account, and the little that was left he had bequeathed to the mathematicians. If he had left everything to Agnes in his will, he would have needlessly hurt the other daughter; if he had discreetly transferred all his money to her account and failed to earmark a symbolic sum for the mathematicians, everyone would have been burning with curiosity to know what had happened to his money.

At first she told herself that she must share the inheritance with her

Immortality

sister. Agnes was eight years older and could never rid herself of a sense of responsibility. But in the end she did not tell her sister anything. Not out of greed, but because she did not want to betray her father. By means of his gift he had clearly wished to tell her something, to express something, to offer some advice he was unable to give her in the course of his life, and this she was now to guard as a secret that concerned only the two of them.

5

s

he parked, got out of the car, and set out toward the avenue. She was tired and hungry, and because it's dreary to eat alone in a restaurant, she decided to have a snack in the first bistro she saw. There was a time when this neighborhood had many pleasant Breton restaurants where it was possible to eat inexpensively and pleasantly on crepes or galettes washed down with apple cider. One day, however, all these places disappeared and were replaced by modern establishments selling what is sadly known as "fast food." She overcame her distaste and headed for one of them. Through the window she saw people sitting at tables, hunched over greasy paper plates. Her eye came to rest on a girl with a very pale complexion and bright red lips. She had just finished her lunch, pushed aside her empty cup of Coca-Cola, leaned her head back, and stuck her index finger deep into her mouth; she kept twisting it inside for a long time, staring at the ceiling. The man at the next table slouched in his chair, his glance fixed on the street and his mouth wide open. It was a yawn without beginning or end, a yawn as endless as a Wagner melody: at times his mouth began to close but never entirely; it just kept opening wide again and again, while his eyes, fixed on the street, kept opening and closing counter to the rhythm of his mouth. Actually, several other people were also yawning, showing teeth, fillings, crowns, dentures, and not one of them covered his mouth with his hand. A child in a pink dress skipped along among the tables, holding a teddy bear by its leg, and it too had its mouth wide open, though it seemed to be calling rather than yawning. Now and again the child would bump one of the guests with the teddy bear.

The tables stood close together, and it was obvious even through the glass that along with the food the guests must also be swallowing the smell of

Immortality

their neighbors' perspiration. A wave of ugliness, visual, olfactory, and gustatory (she vividly imagined the taste of a greasy hamburger suffused by sweetish water), hit her in the face with such force that she turned away, determined to find some other place to satisfy her hunger.

The sidewalk was so crowded that it was difficult to walk. The tall shapes of two fair, yellow-haired Northerners were clearing a way through the crowd ahead of her: a man and a woman, looming head and shoulder over the throng of Frenchmen and Arabs. They both had a pink knapsack on their backs and a child strapped in front. In a moment she lost sight of the couple and instead saw in front of her a woman dressed in baggy trousers barely reaching the knees, as was the fashion that year. The outfit seemed to make her behind even heavier and closer to the ground. Her bare, pale calves resembled a pair of rustic pitchers decorated by varicose veins entwined like a ball of tiny blue snakes. Agnes said to herself: that woman could have found a dozen outfits that would have covered her bluish veins and made her behind less monstrous. Why hadn't she done so? Not only have people stopped trying to be attractive when they are out among other people, but they are no longer even trying not to look ugly!

She said to herself: when once the onslaught of ugliness became completely unbearable, she would go to a florist and buy a forget-me-not, a single forget-me-not, a slender stalk with miniature blue flowers. She would go out into the street holding the flower before her eyes, staring at it tenaciously so as to see only that single beautiful blue point, to see it as the last thing she wanted to preserve for herself from a world she had ceased to love. She would walk like that through the streets of Paris, she would soon become a familiar sight, children would run after her, laugh at her, throw things at her, and all Paris would call her the crazy woman with the forget-me-not....

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

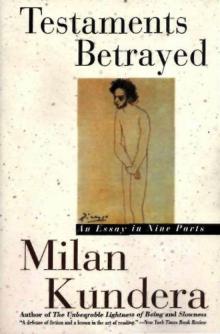

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts