- Home

- Milan Kundera

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Page 2

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Read online

Page 2

"Yes," said Martin with emotion. "You're a true friend. Come, let's go sit down for a while, my legs are aching."

And thus we sat comfortably with our faces turned up toward the face of the sun, and we let the world around us rush on unnoticed.

The Girl in White

Suddenly Martin got up (moved evidently by some mysterious sense) and stared at a secluded path of the park. A girl in a white dress was coming our way. Already from afar, before it was possible to ascertain with complete confidence the proportions of her body or the features of her face, we saw that she possessed unmistakable, special, and very perceptible charm, that there was a certain purity or tenderness in her appearance.

When the girl was fairly close to us, we realized that she was quite young, something between a child and a young woman, and this at once threw us into a state of complete agitation. Martin shot up off the bench: "Miss, I am the director Forman, the film director; you must help us."

He gave her his hand, and the young girl with an utterly astonished expression shook it.

Martin nodded in my direction and said: "This is my cameraman."

"My name is Ondricek," I said, offering my hand.

The girl nodded.

"We're in an awkward situation here. I'm looking for outdoor locations for my film. Our assistant, who knows this area well, was supposed to meet us here, but he hasn't arrived, so that right now we're wondering how to get around in this town and in the surrounding countryside. My friend Ondricek here," joked Martin, "is always studying his fat German book, but unfortunately that is not to be found in there."

The allusion to the book, which I had been deprived of for the whole week, somehow irritated me all of a sudden: "It's a pity that you don't take a greater interest in this book," I attacked my director. "If you prepared thoroughly and didn't leave the studying to your cameramen, maybe your films wouldn't be so superficial and there wouldn't be so much nonsense in them; forgive me." I turned then to the girl with an apology. "Anyhow, we won't bother you with our quarrels about our work; our film will be a historical one about Etruscan culture in Bohemia."

"Yes," the girl nodded.

"It's a rather interesting book�look." I handed the girl the book, and she took it in her hands with a certain religious awe, and when she saw that I wanted her to, she turned the pages lightly.

"Pchacek Castle must surely not be far from here," I continued. "It was the center of the Bohemian Etruscans�but how can we get there?"

"It's only a little way," said the girl, beaming, because her knowledge of the road to Pchacek gave her a little bit of firm ground in the somewhat obscure conversation we were carrying on with her.

"Yes? Do you know the area around there?" asked Martin, feigning great relief.

"Sure I know it," said the girl. "It's an hour away."

"On foot?" asked Martin.

"Yes, on foot," said the girl.

"But luckily we have a car here," I said.

"Wouldn't you like to be our guide?" said Martin, but I didn't continue the customary ritual of witticisms, because I have a more precise sense of psychological judgment than Martin; and I felt that frivolous joking would be more inclined to harm us in this case and that our best weapon was absolute seriousness.

"We don't want, miss, to disturb you in any way," I said, "but if you would be so kind as to devote a short time to us and show us some of the places were looking for, you would help us a great deal�and we would both be very grateful."

"Certainly," the girl nodded again, "I'll be happy . . . but I . . ." Only now did we notice that she had a shopping bag in her hand and in it two heads of lettuce. "I have to bring Mama the lettuce, but it's not far and I'll be right back."

"Of course you have to take the lettuce to Mama," I said. "Well wait for you here."

"Yes. It won't take more than ten minutes," said the girl.

Once again she nodded, and then she went off eagerly.

"God!" said Martin.

"First-rate, no?"

"You bet. I'm willing to sacrifice the two nurses for her."

The Insidious Nature of Excessive Faith

But ten minutes passed, a quarter of an hour, and the girl didn't come back.

"Don't be afraid,'' Martin consoled me. "If anything is certain, then it's this, that she'll come. Our performance was completely plausible, and the girl was in raptures."

I too was of this opinion, and so we went on waiting, with each moment becoming more and more eager for this childish young girl. In the meanwhile, also, the time appointed for our meeting with the girl in corduroy pants went by, but we were so set on our little girl in white that it didn't even occur to us to leave.

And time was passing.

"Listen, Martin, I don't think she's coming back," I said at last.

"How do you explain it? After all, that girl believed in us as in God himself."

"Yes," I said, "and in that lies our misfortune. That is to say she believed us only too well!"

"What? Perhaps you'd have wanted her not to believe us?"

"It would perhaps have been better like that. Too much faith is the worst ally." A thought took my fancy; I got really involved in it: "When you believe in something literally, through your faith you'll turn it into something absurd. One who is a genuine adherent, if you like, of some political outlook, never takes its sophistries seriously, but only its practical aims, which are concealed behind these sophistries. Political rhetoric and sophistries do not exist, after all, in order to be believed; rather, they serve as a common and agreed-upon alibi. Foolish people, who take them seriously, sooner or later discover inconsistencies in them, begin to protest, and finish finally and infamously as heretics and apostates. No, too much faith never brings anything good�and not only to political or religious systems but even to our own system, the one we used to convince the girl."

"Somehow I'm not quite following you anymore."

"It's quite simple: for the girl we were actually two serious and respectable gentlemen, and she, like a well-behaved child who offers her seat to an older person on a streetcar, wanted to please us."

"So why didn't she please us?"

"Because she believed us so completely. She gave Mama the lettuce and at once told her enthusiastically all about us: about the historical film, about the Etruscans in Bohemia, and Mama�"

"Yes, the rest is perfectly clear to me ..." Martin interrupted me and got up from the bench.

The Betrayal

The sun was already slowly going down over the roofs of the town; it was cooling off a bit, and we felt sad. We went to the cafe just in case the girl in the corduroy pants was by some mistake still waiting for us. Of course she wasn't there. It was six-thirty. We walked down to the car, and suddenly feeling like two people who had been banished from a foreign city and its pleasures, we said to ourselves that nothing remained for us but to retire to the extraterritorial domain of our own car.

"Come on!" remonstrated Martin in the car. "Anyhow, don't look so gloomy! We don't have any reason for that! The most important thing is still before us!"

I wanted to object that we had no more than an hour for the most important thing, because of Jirinka and her rummy game�but I chose to keep silent.

"Anyway," continued Martin, "it was a fruitful day; the sighting of that girl from Traplice, boarding the girl in the corduroy pants; after all, we have it all set up whenever we feel like it. We don't have to do anything but drive here again!"

I didn't object at all. Sighting and boarding had been excellently brought off. That was quite in order. But at this moment it occurred to me that for the last year, apart from countless sightings and boardings, Martin had not come by anything more worthwhile.

I looked at him. As always his eyes shone with a lustful glow. I felt at that moment that I liked Martin and that I also liked the banner under which he had been marching all his life: the banner of the eternal pursuit of women.

Time was passing, and Martin said: "It's seven o'clock."

We drove to within about ten meters of the hospital gate, so that in the rearview mirror I could safely observe who was coming out.

I was still thinking about that banner. And also about the fact that in this pursuit of women from year to year it had become less a matter of women and much more a matter of the pursuit itself. Assuming that the pursuit is known to be vain in advance, it is possible to pursue any number of women and thus to make the pursuit an absolute pursuit. Yes: Martin had attained the state of being in absolute pursuit.

We waited five minutes. The girls didn't come.

It didn't put me out in the least. It was a matter of complete indifference to me whether they came or not. Even if they came, could we in a mere hour drive with them to the isolated cabin, become intimate with them, make love to them, and at eight o'clock say goodbye pleasantly and take off ? No, at the moment when Mar-tin limited our available time to ending on the stroke of eight, he had shifted the whole thing to the sphere of a self-deluding game.

Ten minutes went by. No one appeared at the gate.

Martin became indignant and almost yelled: "I'll give them five more minutes! I won't wait any longer!''

Martin hasn't been young for quite a while now, I speculated further. He truly loves his wife. As a matter of fact he has the most regular sort of marriage. This is a reality. And yet�above this reality (and simultaneously with it), Martin's youth continues, a restless, gay, and erring youth transformed into a mere game, a game that was no longer in any way up to crossing the line into real life and realizing itself as a fact. And because Martin is the knight obsessed by Necessity, he has transformed his love affairs into the harmlessness of the Game, without knowing it; so he continues to put his whole inflamed soul into them.

Okay, I said to myself. Martin is the captive of his self-deception, but what am I? What am I? Why do I assist him in this ridiculous game? Why do I, who know that all of this is a delusion, pretend along with him? Am I not then still more ridiculous than Martin? Why should I now behave as if an erotic adventure lies before me, when I know that at most a single aimless hour with unknown and indifferent girls awaits me?

At that moment in the mirror 1 caught sight of two young women at the hospital gates. Even from that distance they gave off a glow of powder and rouge. They were strikingly chic, and their delay was obviously connected with their well-made-up appearance. They looked around and headed toward our car.

"Martin, there's nothing to be done." I renounced the girls. "It's been more than fifteen minutes. Let's go." And I put my foot on the gas.

Repentance

We drove out of B. We passed the last little houses and drove into the countryside through fields and woods, toward whose treetops a large sun was sinking.

We were silent.

I thought about Judas Iscariot, about whom a brilliant author relates that he betrayed Jesus just because he believed in him infinitely: He couldn't wait for the miracle through which Jesus was to have shown all the Jews his divine power, so he handed him over to his tormentors in order to provoke him at last to action; he betrayed him because he longed to hasten his victory.

Oh, God, I said to myself, I've betrayed Martin from far less noble motives; I betrayed him in fact just because I stopped believing in him (and in the divine power of his womanizing); I am a vile compound of Judas Iscariot and of the man whom they called Doubting Thomas. I felt that as a result of my wrongdoing my sympathy for Martin was growing, and that his banner of the eternal chase (which was to be heard still fluttering above us) was reducing me to tears. I began to reproach myself for my overhasty action.

Shall I be in a position more easily to part with these gestures that signify youth for me? And will there remain for me perhaps something other than to imitate them and endeavor to find a small, safe place for this foolish activity within my otherwise sensible life? What does it matter that it's all a futile game? What does it matter that I know it? Will I stop playing the game just because it is futile?

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

He was sitting beside me, and little by little his indignation subsided.

"Listen," he said, "is that medical student really first-rate?"

"I'm telling you she's on Jirinka's level."

Martin put further questions to me. I had to describe the medical student to him once again.

Then he said: "Perhaps you could hand her over to rne afterward?"

I wanted to appear plausible. "That may be quite difficult. It would bother her that you're my friend. She has firm principles."

"She has firm principles," said Martin sadly, and it was plain that he was upset by this.

I didn't want to upset him.

"Unless I could pretend I don't know you," I said. "Perhaps you could pass yourself off as someone else."

"Fine! Perhaps as Forman, like today."

"She doesn't give a damn about film directors. She prefers athletes."

"Why not?" said Martin, "it's all within the realm of possibility," and we spent some time on this discussion. From moment to moment the plan became clearer, and after a while it dangled before us in the advancing twilight like a beautiful, ripe, shining apple.

Permit me to name this apple, with some pomposity, the Golden Apple of Eternal Desire.

Immortality

Immortality Dr. Havel After Twenty Years

Dr. Havel After Twenty Years Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere Laughable Loves

Laughable Loves Symposium

Symposium Ignorance

Ignorance The Unbearable Lightness of Being

The Unbearable Lightness of Being Nobody Will Laugh

Nobody Will Laugh Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts

Jacques and His Master: An Homage to Diderot in Three Acts The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire

The Golden Apple of Eternal Desire Eduard & God

Eduard & God Slowness

Slowness Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead

Let the Old Dead Make Room for the New Dead Farewell Waltz

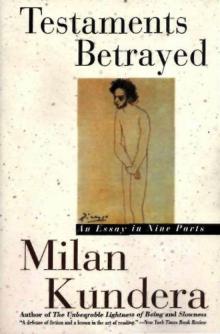

Farewell Waltz Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts

Testaments Betrayed: An Essay in Nine Parts